Home > Miscellaneous > Why I Prefer Permissive Licenses to Copyleft

When I first learned of the existence of copyleft, I was immediately struck by the strangeness of the concept. I wondered why those who supposedly disliked the various restrictions imposed by copyright and wished for more freedom with regard to the use, modification, and distribution of copyrighted works would ever turn to a counterintuitive thing like a copyleft license when there existed many excellent permissive licenses. I was rather surprised when I discovered that, rather than being a small minority, both the number of works released under a copyleft license, as well as the supporters of the practice, were in reality quite numerous, with the latter sometimes defending passionately their use of such licenses. In the course of various discussions with its users and advocates I became aware of the common arguments in its favor, but was unconvinced by any of them; after further research into the topic I still remain so, and continue to maintain my preference for permissive licenses.

In the following I explain my reasons for favoring permissive licenses over copyleft licenses. I am aware that the topic is often discussed in the context of the software world in particular, but here I intend to treat it in a general manner, i.e., with respect to all works to which a license can be applied, whether software or non-software. Note that when I use the term permissive license, I mean those licenses which, besides not imposing the share-alike/heritability/reciprocity requirement that is the distinguishing characteristic of copyleft licenses, also place very few other restrictions regarding how a work may be distributed. For non-exhaustive lists of such licenses, see the Wikipedia page listing some permissive software licenses, as well as the Copyfree Initiative's list of certified copyfree licenses.

The supporters of copyleft state that they wish to defend and preserve freedom; this is undoubtedly a noble goal, and it is one which I also seek above all others. I disagree with the practice of copyleft not because I do not value freedom, but because I treasure freedom so much that I view copyleft as insufficiently free. I have always regarded freedom in large part to be the absence of rules and restrictions, and I would also assert that this is the common-sense definition of the term; hence to argue that adding a restriction (viz., the share-alike requirement) is more free than not adding one is a deeply counterintuitive notion which renders the copyleft conception of freedom a very strange thing indeed. Of course, the copyleft advocates reply that adding such a condition to the license now is necessary to preserve freedom in the future, for it restricts those who would restrict others, but they overlook the fact that the share-alike requirement itself is still very much a restriction that diminishes freedom.

In regard to a reduction of freedom they seem to prefer a certainty to a potentiality—that is, while it is true that applying a permissive license to a work of yours might potentially lead later on to others adding restrictive conditions to their own modified versions, to add the share-alike condition of a copyleft license to your work is to add a restrictive condition at the very start of the process (i.e., at the moment of license application), and thus to make the reduction of freedom a certainty. It is not the case that every permissively licensed work will spawn a proprietary version: it is entirely possible that all derivative versions will also be permissively licensed; but it is certainly the case that every copylefted work, by the inclusion of the share-alike condition, is ipso facto less free—that is, imposes more restrictions—than every work released under a permissive, non-copyleft license.

In the end, I find that I simply cannot accept their incredibly odd definition of freedom. It appears to give greater attention and weight to future possibilities than to present certainties, and to be concerned more with the potential actions of others than with minimizing the restrictions accompanying their own works.

It seems, in fact, that this is a recurring theme amongst them: they possess such a strong hostility towards potential proprietization that, rather than ensuring that their own work is sufficiently free of copyright restrictions, they neglect this and instead preoccupy themselves with reducing the number of proprietary works that could arise. They worry that a work, left unguarded by a copyleft license, could give rise to a derivative version with numerous restrictive conditions, but I fail to see the problem in this: why does it matter so much if your permissively licensed work spawns another proprietary work that is heavily based upon yours? The person who produces the proprietary version cannot, by the mere act of proprietization, ever erase your work, or censor it, or steal it from you, or deprive you of your rights to it; the fruits of your labor are still there, undisturbed, and free for the whole world to experience, modify, and distribute as it sees fit. The only thing that this person has done is produced his own derivative version and subsequently burdened it with stifling copyrights, but he can never force you—or anyone else—to deal with him and his restrictive work; all remain entirely free to ignore him and his proprietary version.

It is plain to see, indeed, that nobody is ever forced to deal with any proprietary work: we select the ones we watch, read, hear, use, experience, etc. through our own choice, and can always ignore them if we so choose. Copyleft therefore sacrifices a degree of freedom for nothing: while it might reduce the stock of proprietary works, in reality we were never forced to deal with such things in the first place, and could have also avoided their constraints upon our freedom simply by ignoring them. In light of this, rather than attempting to minimize the number of proprietary works, should we not instead seek to maximize the number of works licensed under permissive terms? Should we not release more works with very minimal to no restrictions, and thereby provide people with a truly unfettered collection of books, software, music, art, films, and so on? Should we not provide them those options, to which they can turn and thus more readily ignore the proprietary stuff, rather than reducing freedom to destroy monsters which never threatened us in the first place?(1)

Here I should note that a typical copyleft license is still far freer (that is, it has fewer conditions) than a proprietary license, and hence if the world became filled with works licensed under a copyleft scheme, I admit that I wouldn't have much reason to complain. My issue is not that copyleft is oppressive—by absolute standards it is quite free—but that it is not perfect, i.e., that it can become freer still by the elimination of the share-alike condition. One of the chief reasons presented by the users of copyleft in defense of the practice is that it is a useful tool to reduce the quantity of proprietary works, but in the foregoing I have explained that this is a misplaced concern, and that we ought instead to focus on our own works, and apply licenses to them which maximize freedom.

Another argument that I have encountered in support of copyleft, at least in the specific context of computer software, is the one which states that copyleft is necessary to make those who would otherwise proprietize their improvements to a piece of free software instead release their work under a copyleft license, and thus allow the original developer(s) (as well as the wider FOSS community) to benefit from their efforts, since they have already benefited from the efforts of the original developer(s). To this, I reply that such a view is nothing but pure entitlement: for what reason, I ask, does anybody have any obligation to pay back

a benefit which he received at no cost from anybody else? The act of downloading—that is, copying—the source code of a piece of free software imposes zero costs upon its developer, and does not in the slightest deprive him of anything. By their reasoning, is, e.g., every user of GIMP who downloads the program, uses it to produce art, and thereby derives benefit from it now obligated to return the favor

by donating to the developers? Does every user of Emacs who ever finds it slightly useful now owe

the developers something? Such an argument is never seriously entertained in the case of mere use of a piece of software—why, then, does it receive so much attention in the case of development? If a man becomes a rich and famous digital artist solely by using GIMP, few would assert that he owes

something to its developers and/or the FOSS community and must share his good fortune with them; but if the same man downloads GIMP's source code and uses it as a foundation for his own proprietary image-editing software, and becomes rich and famous through selling that, then suddenly they clamor that he has somehow taken without giving back, and justify their use of a copyleft license as an effective method whereby he will be forced to share his work because he owes

them.

In truth, without a cost to the developer I cannot see any valid moral obligation, and a FOSS developer ought never to operate under the expectation that any improvements made by someone else to code that he has previously contributed shall ever be shared with himself or the FOSS community.(2) Certainly it is a nice thing for someone contribute back his improvements, and we may ask, exhort, and even pressure him to do this, but I cannot ever support the use of a technique like copyleft to transform this desire for reciprocity into, in effect, the threat of a lawsuit against anybody who does not wish to share.

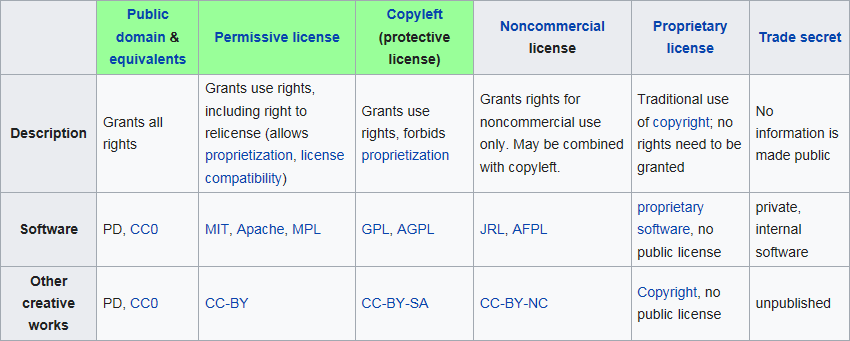

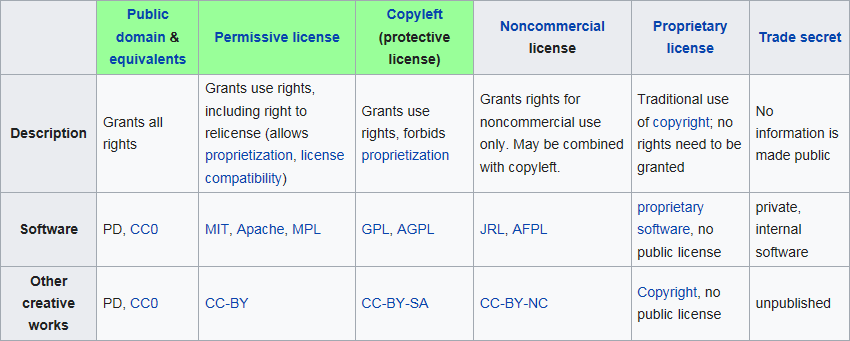

Here I direct the reader to the table in the Wikipedia article concerning free-software licenses, which I have also reproduced below.

In this table various types of licenses are ordered according to the scope of rights they grant; those which grant more are placed further to the left. Traditional copyright occupies the second rightmost column, and it is plainly seen that permissive licenses, which occupy the second leftmost column, are categorized as further away from copyright than copyleft licenses are, which occupy the third leftmost column; thus according to Wikipedia, at least, permissive licenses are more distant from traditional copyright and proprietary licenses than are copyleft licenses.

If the supporters of copyleft tire so much of the restrictions of copyright and proprietary licenses, then why do they still insist on using licenses that remain closer to those which they dislike and oppose so strongly? We are all aware of the views of Richard Stallman(3) and the Free Software Foundation regarding proprietary software—should they not then seek to distance themselves ever further from the thing they detest so much by adopting permissive rather than copyleft licenses? Certainly this is how they can make a bolder statement against restrictive copyright and proprietary licenses. Should they not, indeed, follow this line of reasoning to its logical conclusion, and instead embrace the leftmost column—should they not rather prefer to release all their work into the public domain, or employ a public-domain-equivalent license, both of which constitute the ultimate rejection of copyright law and the proprietary licenses it generates? The copylefters frequently speak of freedom from the many constraints of proprietary licenses, yet they themselves adopt licenses which are quite far from possessing the fewest copyright restrictions, and then proceed to claim that they, in fact, are the ones most vehemently defending freedom and opposing oppressive copyrights.

Here I assume that the proponents of copyleft are, in fact, anti-copyright, or at least heavily critical of the idea and its expression by means of the law, and desirous of comprehensive reform; if they are actually supportive of the current system of copyright law, then this particular argument of mine will not hold any weight with them. I believe it to be a reasonable assumption, however, that there are a good number of them who, by their animosity towards the many copyright restrictions contained in proprietary licenses, either desire for the outright abolition of copyright, or else seek to greatly reduce the scope of the law. To those who advocate for broad reforms of the current system, but who also believe that copyleft licenses are superior to permissive ones, I say that your views conflict with one another; and to those who call for the abolition of copyright laws while simultaneously championing the use of copyleft, I say that your views descend into outright contradiction.(4)

The entire mechanism of copyleft relies upon the system of copyright law: enforcing the share-alike provision of a copyleft license requires bringing lawsuits for copyright infringement against violators. For those who purport to oppose copyright, and who see the current framework as oppressive and immoral, why do you nevertheless support and employ a technique that uses the full power of that framework? How can you be so comfortable with suing, or at least potentially threatening to sue, somebody for copyright infringement, of all things? Perhaps, again, not all copyleft proponents are actually troubled by the current copyright system and wish to change or resist it, but for those who are—and I believe that there are not a few of them in the world—I urge them to be consistent by abandoning copyleft in favor of permissive licensing (and maybe even the public domain) and thus adopt a stronger stance against the restrictions characterizing proprietary licenses and, ultimately, the system of copyright they so greatly dislike.

Finally, there is the fact that copyleft licenses are generally far lengthier than permissive ones: for instance, both the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Public License and version 2 of the Mozilla Public License are over 2,300 words, and meanwhile version 3 of the GNU General Public License (GPL)—which is often considered the quintessential copyleft license—is over 5,600 words. This may be contrasted with, e.g., the permissive licenses certified by the Copyfree Initiative, none of which, besides two somewhat lengthy outliers (the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication, which is 1,066 words, and the Lucent Public License Version 1.02, which is 1,749 words), exceed 400 words—in fact, the overwhelming majority of them do not exceed even 300 words.(5)

I don't praise the brevity of these permissive licenses simply out of a lazy unwillingness to read long documents: copyright licenses have legal significance, and the longer they are, the more cumbersome and tricky it becomes to apply, enforce, or even understand them. Again I assume, like in the previous section, that many copyleft advocates either wish for thorough reforms of copyright law, or even seek to abolish it entirely; at the very least, I think it is a very reasonable assumption that many find the current state of the law excessively complicated, and desire for simplification and greater clarity. Again I find hypocrisy between their professed beliefs and their actions: they state that they want to reduce or eliminate the burdensome complexity of copyright law but willingly perpetuate—at times with much enthusiasm—the existing system's complexity by not releasing their work under short, simple, and straightforward permissive licenses, but instead turn to lengthy copyleft licenses which can only lead, by their inclusion of more conditions, to more complications in the future.

I need not repeat in detail here the issues arising from the use of copyleft licenses and the old criticisms accompanying them, such as the notion of a viral license

or the matter of license compatibility, the latter of which is often a complex exercise in the case of a copyleft license (see, for example, Stallman's almost comically long-winded exposition on the subject), but a simple task in the case of many permissive licenses. I cannot imagine why anyone would ever wish to surround the product of his hard efforts with legal complexities that make it more difficult for others to use and enjoy it, rather than minimizing such absurdities through permissive licensing and thereby promoting the free sharing and spread of his work.(6)

I myself prefer the WTFPL above all others, and have elected to release every page on this site under it. It is a public-domain-equivalent license, and hence grants the maximum amount of freedom to others—that is, it imposes no restrictions whatever on how they may use, copy, modify, and distribute the written material on my site. As I have explained in another page, I selected the WTFPL over other similar licenses (and also over a formal dedication into the public domain) because of its brevity, humor, and general applicability, but this is merely a matter of personal taste; I find all public-domain-equivalent licenses, as well as a public domain dedication and the least restrictive of the permissive licenses, to be excellent and highly commendable choices. I am slightly less (but still greatly) approving of the more restrictive non-copyleft permissive licenses, and substantially less approving of the concept of copyleft and its implementation in the form of the various copyleft licenses. As long as permissive licenses exist, I do not ever foresee myself using a copyleft license, as I find them to be unacceptably constraining and hence too near the traditional use of copyright.

As regards copyright itself, I have never liked it; I have always perceived it as a repressive set of laws which reduce freedom, and recently I have also come to apprehend it as unnecessary, absurd, and illegitimate. My final goal is the abolition of copyright, but I realize, of course, that this at present is only a distant dream; and so long as I continue to live under the current system of copyright, I wish to distance myself as far away as possible from its workings. In consequence I utterly refuse to saddle anything I produce with any copyright restrictions whatever: I do not believe such restrictions are justifiable, and hence I would not dare apply them to my own works and thereby taint them. This is why I reject proprietary, copyleft, and even the more restrictive of the permissive licenses, and instead release my work under a public-domain-equivalent license: it is only then that I have, in effect, placed it outside the framework of copyright, and thus avoided participating in the system in any manner. With respect to any of my works, at least, when others approach them it is like copyright law does not even exist, and they are free to do as they please—this was very much my intent, and such a happy state of affairs does not exist in the case of a copylefted work.

What has perhaps surprised me the most about the copylefters is their seeming lack of hesitation to resort to the legal system. They readily embrace long licenses with many complicated terms, and have no qualms about using the law to enforce those licenses; there are even whole organizations, like the Software Freedom Conservancy and the Software Freedom Law Center, dedicated to filing lawsuits for copyright infringement in order to ensure compliance with the requirements contained within copyleft licenses. I cannot ever imagine myself suing anybody for a thing like copyright infringement, for I view the very idea as nonsensical and something which should not even be illegal, and in general I have a strong aversion to involving the law and the government in any of my affairs. They speak frequently of freedom, but when anyone who wishes to copy or use their work must follow the share-alike condition of their licenses or else potentially face them bringing in the full force of the law to compel this, how can they seriously contend that copyleft is freer than permissive licensing?

I have also heard some of them cite their own rational self-interest as a reason to use a copyleft instead of a permissive license—e.g., in the context of software in particular, they state that copyleft licenses, unlike permissive ones, ensure that those who build upon their code share back the improvements with them, thus allowing them to receive something after they have first given—and still others simply have a bizarre personal desire to make it difficult for a corporation to include their code in its products.(7) They might say to me that I act against my own self-interest by not copylefting, for in so doing I expose myself to the possibility of essentially performing free labor for somebody who takes my work and incorporates it into his own proprietary derivative version, and who afterwards does not even return the favor by granting me the same level of freedom with his work that I initially granted to him with mine.

Such an appeal to self-interest, however, is very similar to one I can imagine a defender of copyright putting forward. It is very easy to conceive of someone who enthusiastically proprietizes his work declaring me a fool who acts contrary to his self-interest because I have willingly waived all my rights to my work which the body of copyright law has furnished me, and that I ought to act rationally by instead choosing to retain full control over its use, modification, distribution, etc., rather than permitting everybody to do whatever they please with the fruits of my labor. In truth, I can discern no essential difference between these arguments, for they both assert, at bottom, that I have the option to turn existing copyright law to my own personal advantage, and that it is irrational for me not to do so. To both groups, I simply say, again, that I absolutely refuse to partake in the system of copyright—even for my own self-interest—and that I care far more about maximizing freedom with respect to the use of my works. I don't mean to say, of course, that it is a bad thing to act in your own self-interest, but if you admit that this is your reason for applying a copyleft license to your work, then how can you still profess to be defending freedom and claim the moral high ground above those who use proprietary licenses, whom you accuse of selfishly using the full extent of copyright law for their own personal benefit? And if you then reply that you copyleft both to defend freedom and for your own personal advantage, then I reply in turn that this is perfectly fine—but do not then declare that you are a more passionate fighter for freedom than me or most other users of permissive licenses, for we sacrifice our own interest for the sake of freedom far more than you do.

Of course, the copyleft supporters may also argue that the freedom lies in the ends, not the means: so long as the number of works released under a proprietary license is lessened, then the additional restrictions of copyleft are justified. They may claim that they are using the system against itself—that is, that they use the present framework of copyright law to defeat the restrictive product of that framework, viz., proprietary licensing—but I cannot agree with such a method. In the end, I cannot bring myself to use copyright to fight copyright by copylefting my work, for then I will have inevitably and wrongfully restricted the freedom of others by using the laws of a system that I view as illegitimate. I find that the ultimate rejection of the current copyright system is the complete avoidance of it, and this entails the absolute refusal on my part to apply any copyright restrictions to my work, including the share-alike requirement of copyleft.

Ultimately, however, it is often wise to return to our common sense, and to give heed to its conclusions. I return again to the issue of freedom, which is a thing valued highly by both groups, and make a final appeal to intuition: what is more free, a short, simple permissive license which imposes few to no restraints or conditions on how the work to which it is applied may be distributed, or a much longer and more complex copyleft license containing many more restrictions, always including the share-alike condition but sometimes having even more than that? Which is less likely to spawn copyright infringement suits and bog down both sides in litigation? Which is more conducive to getting a work freely shared, modified, and built upon due to the extreme ease of satisfying its licensing requirements (if any even exist in the first place) and hence avoiding the threat of getting into legal trouble? In regard to freedom the copyleft conception is suspiciously counterintuitive, whereas permissive licenses, with their minimal restrictions, at once strike our common sense as being the freer choice.

I emphasize also that this piece should not be interpreted as an attack against copyleft or its users/supporters. On occasion, it is true, my criticisms have been sharp and forceful, but I have refrained from being mocking or insulting because, in the end, I agree with the copyleft crowd more than I disagree with them. A copyleft license is undoubtedly far, far freer and better than any proprietary one, and I would still view quite favorably anyone who chooses to release his work under the former, because it is plain to see that the advocates of copyleft, like the advocates of permissive licensing, cherish freedom and loathe copyright restrictions.

The disagreement, I think, lies in the groups' differing approaches: the copyleft users seem to concern themselves with proprietization above all else, and seek to prevent its spread as much as possible. They bring the fight to their enemies, so to speak, and have no objections to using their weapons against them; they are willing to sacrifice a degree of freedom in their own works by putting some conditions and requirements regarding their use if it can render more difficult the production of proprietary derivative versions. In their world, perhaps there are fewer proprietary works; but, at the same time, no book, song, painting, program, film, or other work is truly free—the share-alike requirement always looms large over anybody who wishes to copy, modify, and distribute their stuff. For me and many others this is greatly unsatisfying: we look for true freedom, but can never find it, and instead must settle merely for free enough

.

In a world of permissively licensed works there is true freedom. We do not concern ourselves too much with the actions of others, but focus instead on ourselves, and with what each one of us can do to maximize the freedom accompanying our own works. We worry not about whether this or that person will proprietize what we have made; our aim instead is to carve out our own alternative, parallel world of truly unfettered works to compete with the proprietary material. If the collection of proprietary works consequently grows, then this is unfortunate, but so be it: for it is far more important that there be a body of works wholly without restrictions, to which people can turn when they tire of the constraints of the proprietary, and hence taste a real freedom which is not offered by copyleft. Our vision is not necessarily one of minimizing the number of proprietary works, but of maximizing the supply of unequivocally free works through deed and advocacy: we license our own works under permissive terms, and then proceed to persuade those who would otherwise proprietize theirs to do the same. We do not make use of their tools against them, for then nobody's works will be completely free and unencumbered; unlike the copylefters, we do not settle for a middle ground, but pursue freedom to its fullest and purest expression, for in its true form it is a thing to be treasured indeed.

I believe that our world is the more desirable one, and I invite the copyleft crowd to join us in it—but I only beckon to them, and do not reach out and pull them in; I lead by example, not by force of the law; I exhort, but do not demand: such is the true permissive spirit.

Non-free software issuessection.

Advancement Through License Simplicity. I should note that the essay does not use the term permissive license, but rather copyfree, the latter (I would assume) in conformance with the Copyfree Initiative's precise definition of the word. Regardless, there is still a good deal of overlap between the two terms, and in neither is the share-alike requirement characteristic of copyleft licenses present, though, according to the Copyfree Initiative, copyfree is more a specific and strict label than permissive.

make corpos seethe. His comment was made more for humor than anything else, but nevertheless I still suspect that many proponents of copyleft (excluding my friend, of course, who is a fine fellow) are motivated to use those licenses partly because they have some puerile obsession with

resistingthe

evilcorporations/businesses.